Molecular Ecology in the Austrian Alps

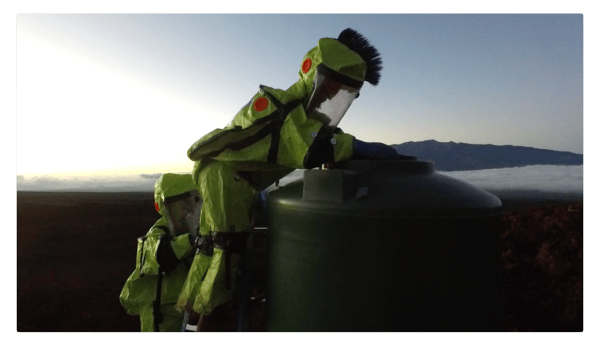

At the University of Innsbruck in Austria, undergraduate biology students are gaining hands-on molecular field experience in the Alps. Professor Birgit Schlick-Steiner, head of the Molecular Ecology research group, leads 120 students every summer in a practical application of molecular ecology, part of a four-day program training the students in eight different areas of biology. Professor Schlick-Steiner’s course requires students to take samples of the ant Formica exsecta and perform a DNA extraction. Students must then perform a PCR to test for the intra-cellular parasite Wolbachia.

Wolbachia are parasitic bacteria that infect arthropods and can have various effects on the infected organism, most notably on their reproductive ability. Since Wolbachia live in the cell’s cytoplasm, they are passed through the egg to offspring when an infected female reproduces. Depending on the strain of Wolbachia and the organism infected, Wolbachia can have a range of effects that help increase its own transmission, from feminizing males, to male-killing, to killing the offspring of uninfected females fertilized by infected males. Learn more about Wolbachia here.

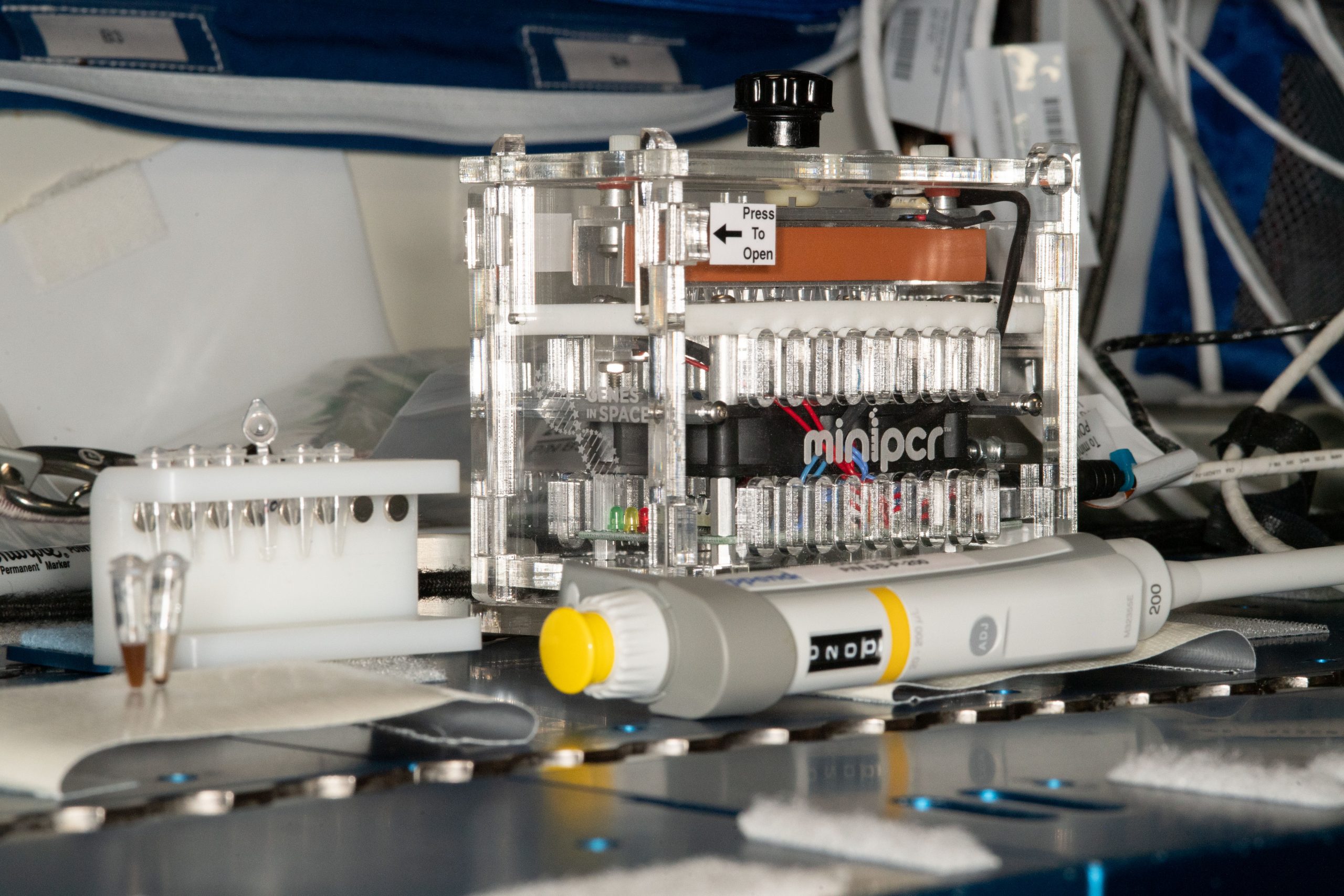

After the students amplify Wolbachia DNA through PCR, they test for specific restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) in order to distinguish between different Wolbachia strains found in the sampled ants. The ants on this particular mountain are known to be infested with several strains of Wolbachia providing a complex system of interacting life history, symbiotic and ecological factors to investigate.

All of this occurs in just 3 hours thanks to extra-fast enzymes and the portability of the miniPCR™ thermal cycler powered by a camping battery! Using this equipment, students get to see firsthand how molecular techniques can be used to solve ecological questions in the field. Professor Schlick-Steiner and her students must carry their entire portable lab in two boxes, and therefore need lightweight and durable equipment for packing in and out of the mountains. Professor Schlick-Steiner says that her work “would simply not be possible without miniPCR.”

Even with the proper equipment, Professor Schlick-Steiner knows firsthand that field work can be unpredictable. She recalls that in the first year of this course her students saw bands on their gel, but only coming from two and a half of their lanes. They were quite confused as to how bands could show up on half of a lane. It turns out that the table the gel was sitting on was uneven and some of the PCR product had ran out of the gel and into the buffer. Since then they have always brought a small level with them on their field expeditions.

When asked about the future, Professor Schlick-Steiner sees the use of molecular techniques for solving ecological problems becoming increasingly important in both research and conservation efforts. You can learn more about the Molecular Ecology research group at the University of Innsbruck here.

— Jake Rozak

Photos credit: Prof. Birgit Schlick-Steiner